What is the truth about the network? And what might it tell us in our current situation? After five years of translation and fine-grained updating, Sebastian Giessmann’s seminal book on The Connectivity of Things: Network Cultures since 1832 finally came out in October 2024 with MIT Press. The full text is available in open access.

While the translated book’s historical narrative is deeply rooted in developments of 19th and 20th century infrastructural history, it is also a key work of German media theory. There’s much to discuss here for historians of technology, be it the notion of “cultural techniques,” the seemingly Western grounding of network practice and thought, and the in/visible work of networking in material cultures itself.

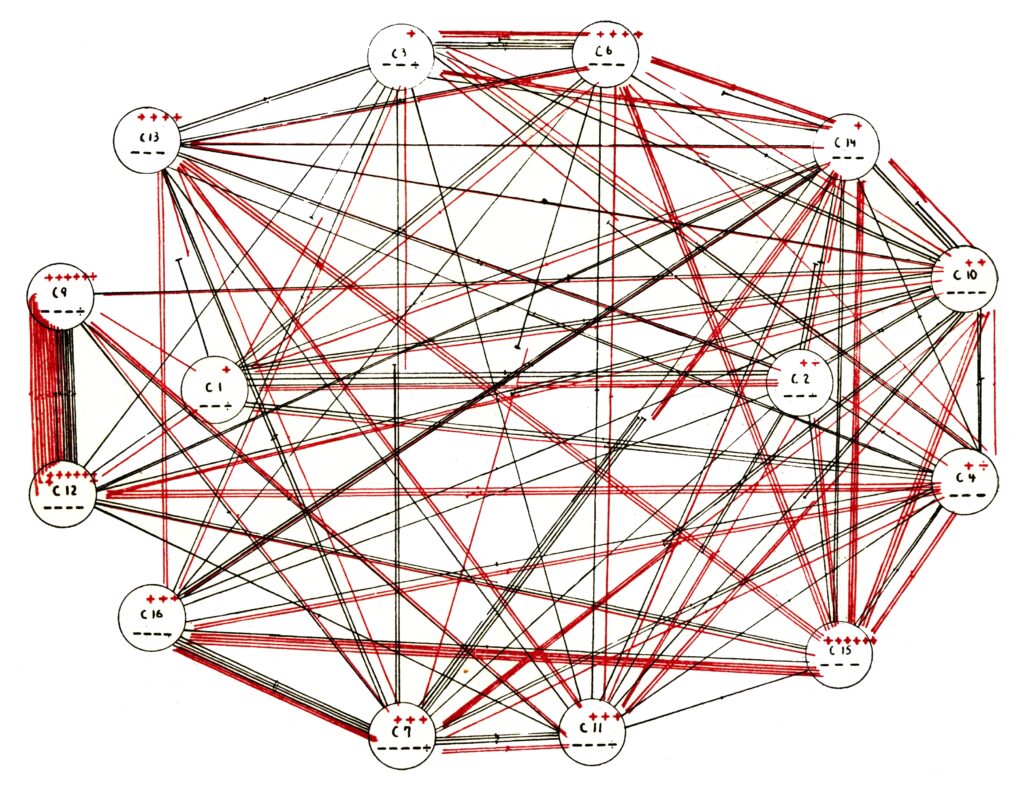

Connectivity is a book full of in-depth case studies that deserve a closer look, be it the relation between networks and colonial power in the case of French Saint-Simonianism, be it the early history of the telephone network, visual histories of network diagrams, the mobilities of the London Tube Map, Western and Eastern styles of logistics, and the unlikely inception of the ARPANET. It might be said that networks are a core cultural technique to allow for the migration of people, signs, and objects, which includes their disconnection. Connectivity of Things finally gives us a history that actor-network theory never dared to write itself.

We invite everyone at SHOT in Luxembourg to join the discussion, both in person and per hybrid participation. Our author-meets-critics session will combine key critical questions towards the book, and shall provide insights into the intricacies of such an (un-)timely and complex translation endeavor.

On The Connectivity of Things: Network Cultures since 1832

Author-meets-critics: Sebastian Giessmann (Siegen), Monika Dommann (Zurich), Cyrus Mody (Maastricht), Elizabeth Petrick (Rice), and Thomas Haigh (Wisconsin-Milwaukee)

Society for History of Technology Annual Meeting 2025

„Technologies of Migration – Migrating Technologies“

Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

Friday, October 10

12:55 PM – 2:10 PM