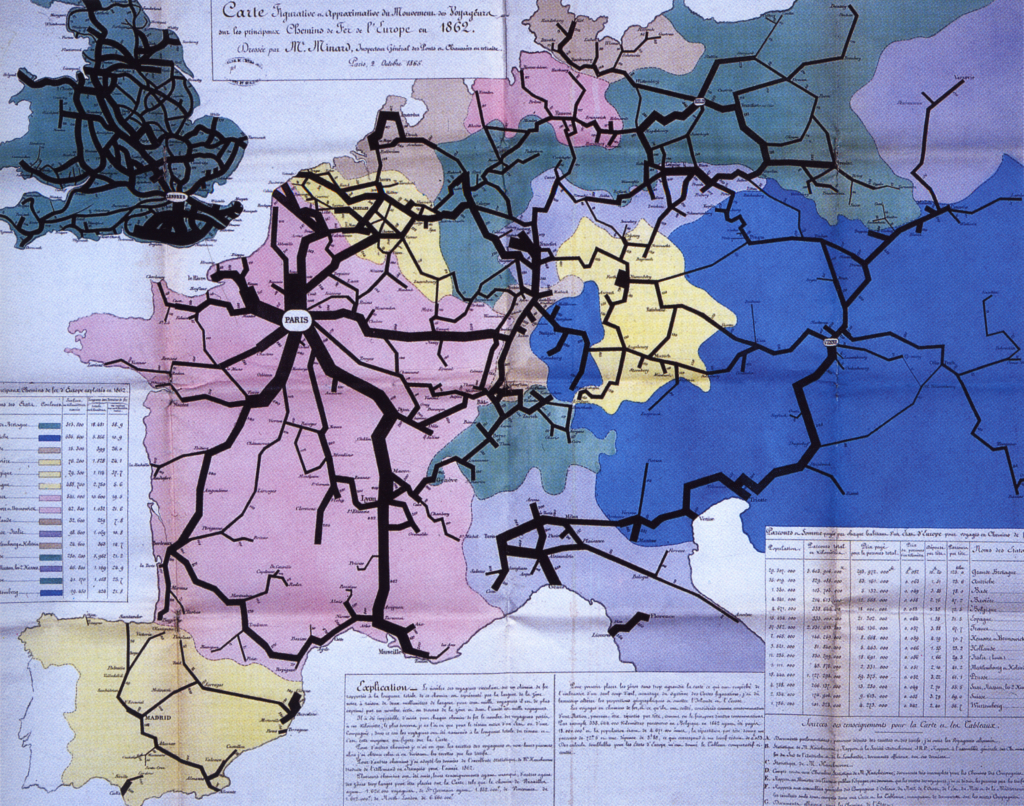

Unsere sozialen Netzwerke basieren auf materieller Kultur, aber zugleich vergessen wir das verbindende – und trennende – Netz, wenn wir kooperieren und kommunizieren. Dieses Verschwinden gehört zur Medialität der Netzwerke untrennbar dazu. Aber ihre materiell-symbolische Konstitution tritt immer wieder zu historischen Wendepunkten in den Vordergrund.

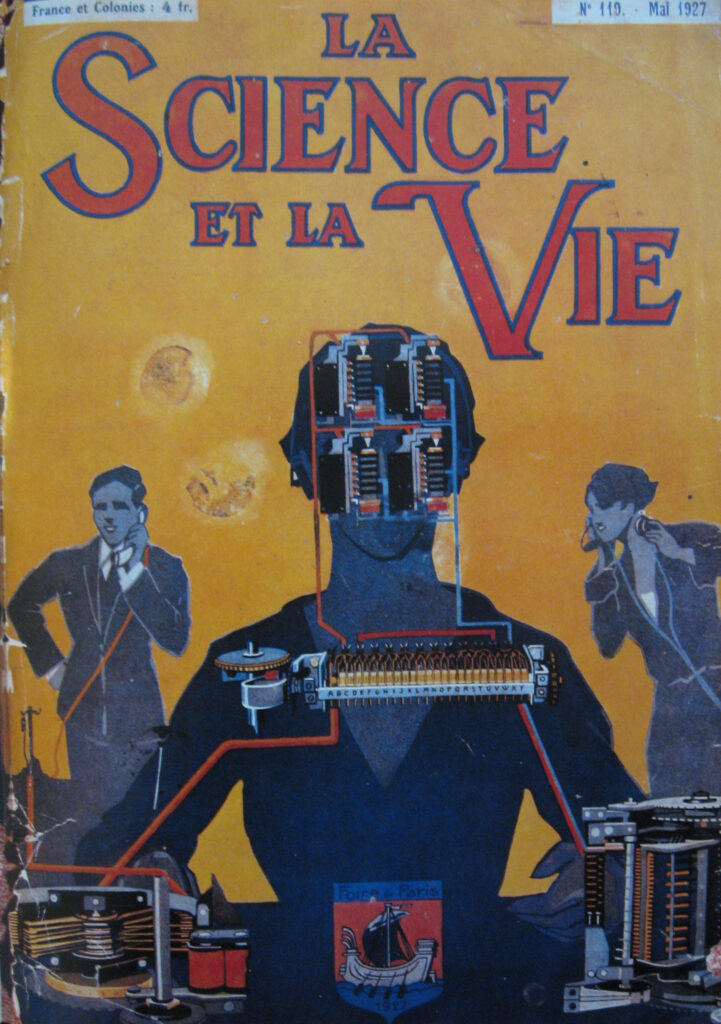

Formalisierte Netzwerke treiben nicht nur die Verbindungslogiken von Social Media an, sie sind auch zur Bedingung für weitere rezente Medienentwicklungen geworden, die Sprache, Texte, Bilder, Töne, Filme und Computercodes unter neue Netzwerkbedingungen stellen. Mit der datenintensiven Entwicklung von Algorithmen maschinellen Lernens ist die „network science“ in eine neue Phase eingetreten, die ich – mit aller gebotenen Vorsicht – die siebte Schicht der Netzwerkgeschichte nenne.

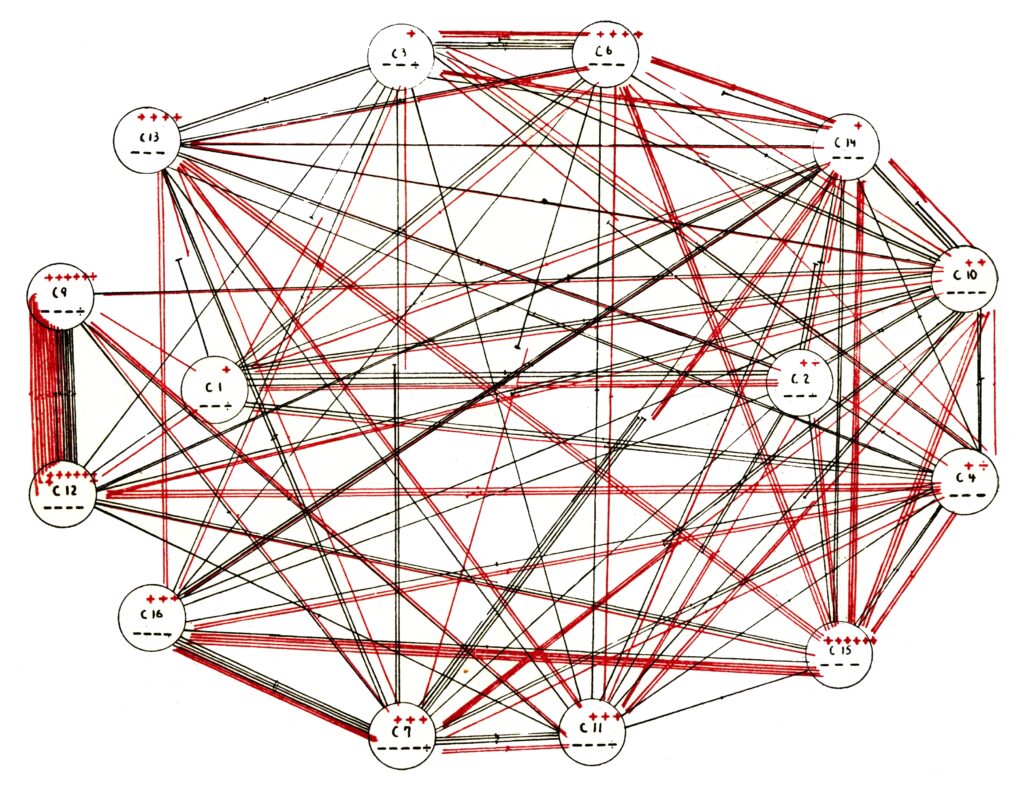

Durch konnektionistische Rechenpraktiken, die auf künstlichen neuronalen Netzen beruhen, ist seit 2012 das Phänomen der lange als gescheitert gegoltenen „Künstlichen Intelligenz“ zurückgekehrt. Galt im maschinellen Lernen zunächst statistischer Sprach- und Bildanalyse durch neuronale Netze die Aufmerksamkeit, ist mit den großen Sprachmodellen seit 2017 ein neuer, „generativer“ Modus der medialen Produktion entstanden. Dieser variiert vor allem bestehende cultural patterns, die vorher einer (formalen) Netzwerkanalyse unterzogen worden sind, um dann aufs Neue Muster zu generieren, die aber lediglich auf Wahrscheinlichkeiten beruhen.

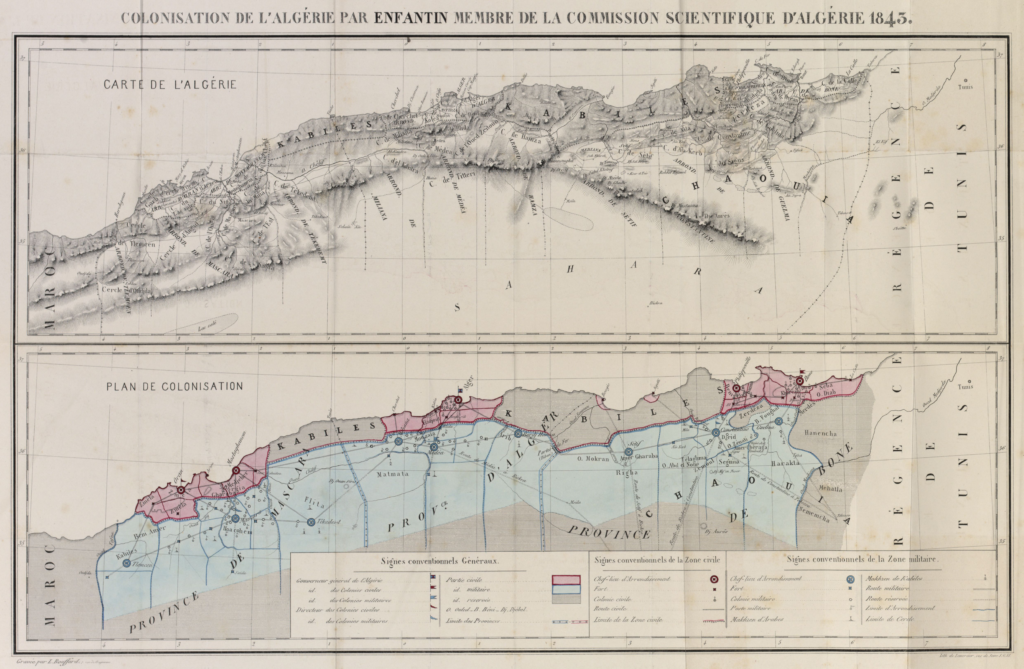

Die Akteur:innen dieser Transformation, ob nun in ihrer nordamerikanischen oder chinesischen Variante, investieren massiv in den Ausbau ihrer geopolitischen Netzwerkmacht. Sie beruht weiterhin auf materiellen Faktoren: Künstliche Intelligenz benötigt energie- und kostenintensive Rechenzentren, um auf allen digitalen Geräten in Quasi-Echtzeit verfügbar zu sein. Sie bleibt auf ständig neue Datenressourcen angewiesen, die durch die Nutzer:innen in unsichtbarer Arbeit miterzeugt – oder wie jüngst im Falle von Metas Training des Sprachmodells Llama – gleich durch Big Tech extraktiv geraubt werden.

Mit konnektionistischer KI, die mit Sicherheit künstlich, aber eben nicht biologisch intelligent ist, steht die Beschreibbarkeit und Analyse dessen, was wir Medien und Kulturtechniken nennen, selbst auf dem Spiel. Dem ins Innere der Medien gewanderten Netzwerk werden wir nur auf die Spur kommen, wenn wir seine politische Ökonomie samt Datenkolonialismus, seine Rückwirkung auf unsere sozialen Medien, aber auch das opake Rechnen mit künstlichen neuronalen Netzen besser verstehen.

Zuerst erschienen im studentischen Magazin Seitenspiel, Potsdam: Europäische Medienwissenschaft, 2025, S. 9.